|

Manmade beaches in Cape May have been a fact of life for 20 years this year.

This article first ran as Beach Replenishment – A Blessing or a Curse

in Cape May Magazine, June

2007.

Replenishment photos appear courtesy of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

You are lying on the beach on Cape

Island. The breezes plant salty kisses. The sun caresses your skin. The ocean

water tickles your toes. The sound of the sea lulls you into oblivion.

The Island’s beautiful tide-washed

strand creates a place for the very best of natural experiences, but can you

believe most of this seascape is man-made?

The reality is that engineers have

been altering the tip of New Jersey for 100 years. The reality is that engineers have

been altering the tip of New Jersey for 100 years.

They dug the current 500-acre Cape

May Harbor with mammoth dredges starting in 1903, spreading the dredge spoils

over 3,600 acres of wetlands and oyster beds to create the new East Cape May

development.

The Cape May Inlet jetties

(formerly called Cold Spring jetties), were

completed in 1911, their long arms reaching 4,500 feet into the Atlantic, at the

mouth of the harbor. These inlet jetties are

devils in the struggle against beach erosion.

During World War II, with German

submarines torpedoing ships off Cape May, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in a

wartime emergency act, sliced across the peninsula from the Coast Guard base to

Delaware Bay, digging a three-mile canal to protect U.S. military maneuvers.

Now fast-forward to the 1980s. It

is sad to see that Cape Island beaches are mere slivers of what they were when

the Lenni Lenape Indians, the Unalachtigo, (meaning people who live by the

ocean) fished and hunted the high dunes and broad beaches.

The fast-eroding seashore had

become a major political-economic issue. Energetic young visionaries all around

Cape May were restoring Victorian structures, converting them into comfy B&Bs.

The city was enjoying its new-found halo as a National Historic Landmark.

Positive publicity went nation-wide. Yet the buzz in the tourist industry

produced a big negative: Cape May is a pretty town. Great architecture, nice

gardens, good restaurants. But the beaches are lousy. “You had to plan your

vacation around the tide table and move your blanket inland every five minutes,”

says Vicki Clark, executive director of the Cape May County Chamber of Commerce. The fast-eroding seashore had

become a major political-economic issue. Energetic young visionaries all around

Cape May were restoring Victorian structures, converting them into comfy B&Bs.

The city was enjoying its new-found halo as a National Historic Landmark.

Positive publicity went nation-wide. Yet the buzz in the tourist industry

produced a big negative: Cape May is a pretty town. Great architecture, nice

gardens, good restaurants. But the beaches are lousy. “You had to plan your

vacation around the tide table and move your blanket inland every five minutes,”

says Vicki Clark, executive director of the Cape May County Chamber of Commerce.

Pressure was put on the Army Corps

of Engineers. The Corps finally admitted a big mistake had been made in

anticipating the negative aspects of cutting through the canal 45 years earlier.

The Corps agreed that the design of the canal, with the extended older jetties,

had a devastating affect on Cape Island beaches.

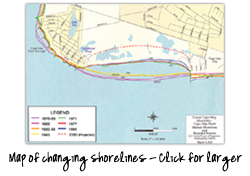

“It’s obvious from aerial

photographs that the north jetty creates a severe offset that interferes with

the river of sand that flows offshore,” says Army Corps Project Engineer Dwight

Pakan. “The sand gets trapped at the north jetty and impedes the natural drift

southward toward beaches in Cape May City, the Cove, the Meadows, the Lighthouse

beach and Cape May Point.”

It took an act of Congress to

decide that what the government had mistakenly taken away, it must return to

Cape Island. The Army Corps of Engineers got the assignment in the late 1970s to

design a beach replenishment project that would dramatically change the

landscape and life of locals and vacationers.

First evidence of new sand from

Poverty Beach to Pittsburgh Avenue appeared during the winter of 1991. Giant

mountains of sand were pumped in from a dredge offshore, then sculpted and

graded. The monster sand-moving equipment appeared in the mist and fog like

dinosaurs hulking against the sea. First evidence of new sand from

Poverty Beach to Pittsburgh Avenue appeared during the winter of 1991. Giant

mountains of sand were pumped in from a dredge offshore, then sculpted and

graded. The monster sand-moving equipment appeared in the mist and fog like

dinosaurs hulking against the sea.

“There was no beach at all,” says

Pakan. There were the massive concrete and boulder seawall and groins reaching

into the ocean that had been constructed in the 1940s to protect beach front

properties. “We buried them with sand to shape the new beach.” It stretched from

the Coast Guard base south past the deteriorating 1908 Christian Admiral Hotel,

a mere shell of its former self, the once-grand centerpiece of the East Cape May

Real Estate Company development.

Since 1989, the cost of rebuilding

and replenishing Cape Island beaches has topped $50 million with estimates of

more than $100 million to continue replenishing in the future. More than 33

million cubic yards of sand have been redeposited from offshore to create 5.7

miles of expanded beach from the Coast Guard base to Cape May Point. This new

seascape today remains very political, experimental, controversial and one of

the most expensive manufactured beaches in the world.

Depending on which side of the

blanket you are sitting, beach replenishment is considered a blessing – or a

curse.

Taxpayers from all over America

foot the multi-million dollar bill to build the beaches. And taxpayers, through

Congress, have promised to continue paying for replenishment for 50 years after

the initial projects are completed.

Despite the commitment, every year

is a struggle to secure the money. “It’s a forever challenge to convince midwest

and mountain representatives that beach replenishment is not about a sun tan,

but bread and butter issues,” says Congressman Frank LoBiondo “If there’s no

beach, there are no tourists, no businesses, no jobs, the ripple effects are

devastating. Likewise, the beaches and dunes protect lives and property. Without

this system in place we would suffer the consequences of a storm direct hit.

Remember Katrina?”

There is no debating that beaches

are the lifeblood of the economy. The lust for the sea experience generates

billions in vacation dollars and real estate fortunes. Many blessings, indeed.

But there is danger lurking along

man-made beaches where high surf breaks closer to the beach and there are

sudden drop-offs and step-offs in the ocean where the imported sand has not

stabilized to form a gentle slope found on natural beaches. There are invisible

cavities near stone groins, aging steel and wooden piers that have been

blanketed with sand.

Veteran beach lovers in Cape May

Point were angry the first summer after the 2004 winter beach replenishment.

They were vocal about dangerous holes and drop-offs, new rip currents and rough

imported sand. They were accustomed to narrow tide-cooled sloping beaches of the

finest sand in the world. Veteran beach lovers in Cape May

Point were angry the first summer after the 2004 winter beach replenishment.

They were vocal about dangerous holes and drop-offs, new rip currents and rough

imported sand. They were accustomed to narrow tide-cooled sloping beaches of the

finest sand in the world.

Former Mayor Malcolm Fraser, an

engineer, told the upset beachgoers, “Patience. We need to wait for nature to

take its course stabilizing the new beach. The tides will wash over it,

hardening the beach in place. Natural sands will drift in, and begin to collect

as is to happen with successful beach replenishment.”

Patience and stubbornness are

Fraser traits that have been fundamental to building the 2.7 miles of new beach

from the 3rd Avenue Cove in Cape May to Cape May Point.

The nuns at St. Mary By-the-Sea

prayed for a miracle when they realized their massive picturesque summer retreat

house at the Point was threatening to fall into the sea.

(Cape May Magazine, Fall 2006)

You could say it’s a miracle that Mayor Fraser was able to use an obscure

executive order signed by President George Bush in 1991 allowing the Army Corps

a loophole to protect threatened, but critical wildlife habitats. In this case,

it is Cape May’s Migratory Refuge.

Mayor Fraser’s motivation? Without

success his little town of 240 cottage dwellers might wash away in major storms

as neighboring South Cape May did a century ago. The World War II bunker where

he proposed marriage to his wife in 1953 now stood on pilings in the surf. The

wetlands, known as the Lower Cape Meadows, home to the Migratory Bird Refuge at

Cape May Point State Park, near the Lighthouse,

were inundated with salt water when Hurricane Gloria hit in 1985 and broke

dunes. Storms in 1991 breached rebuilt dunes a half dozen times and contaminated

the fresh water. Mayor Fraser’s motivation? Without

success his little town of 240 cottage dwellers might wash away in major storms

as neighboring South Cape May did a century ago. The World War II bunker where

he proposed marriage to his wife in 1953 now stood on pilings in the surf. The

wetlands, known as the Lower Cape Meadows, home to the Migratory Bird Refuge at

Cape May Point State Park, near the Lighthouse,

were inundated with salt water when Hurricane Gloria hit in 1985 and broke

dunes. Storms in 1991 breached rebuilt dunes a half dozen times and contaminated

the fresh water.

Sometimes it seemed a losing

proposition, but Mayor Fraser never gave up. “I promised my bride 53 years ago

she would always live in Cape May Point,” he says. “It was a pre-nuptial

agreement.”

A decade of studying, politicking

with Congress and planning with the Army Corps of Engineers resulted in the 2004

project that pumped in 1.7 million cubic yards of sand at the cost of 15 million

dollars. High dunes were constructed over massive cores of gravel and clay.

Where there once was sea and the ghosts of South Cape May, a wide expanse of

beach stretched toward the Atlantic. The Lighthouse beaches quadrupled in size.

Dunes now protect the nuns’ 150-year-old St. Mary’s and Point cottages. And the

Army bunker where Mayor Fraser proposed marriage has sand around its feet.

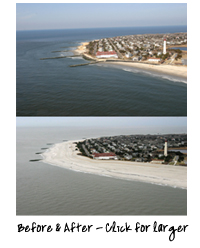

The most dramatic change in the

landscape is in East Cape May where developers went bankrupt at the turn of the

century. Once the new beaches were built in 1991, the neighborhood flooding that

happened with every fierce nor’easter and hurricane became a bad memory. When the Christian Admiral was torn down in 1996, the monopoly game began in earnest. with every fierce nor’easter and hurricane became a bad memory. When the Christian Admiral was torn down in 1996, the monopoly game began in earnest.

Called the Admiral Beach Estates,

the site of the old hotel was subdivided into 26 lots. Beachfront lots

sold for more than $400,000. Now, 10 years later, there are a couple dozen new

multi-million dollar mansions, and one beachfront lot remaining. It was listed

recently at more than $3.5 million! Some of the lots have been flipped several

times, fortunes being made. Residents were living on highly escalated land, but

they lost their private tiny beaches hidden by the seawall.

As this

story is written, a mean nor’easter is battering Cape Island. It’s dusk at Cape

May Point. Malcolm Fraser pulls on his slicker and boots, a slight figure,

bracing against 55

mph winds at a beach look-out. Into the darkness he

sees his beaches are holding. He returns to his cottage on Lake Lily. “We

survived another one,” he says to his wife.

Beach Replenishment Update

That rolling thunder heard in

Cape May this winter brings promise of more sand on the beaches next summer. As

many as 360 triple-axel trucks, loaded with sand, are tooling down Delaware

Avenue each day to the Coast Guard base until 126,000 cubic yards, or 151,640

tons of sand is dumped there. The truck cavalcade is expected to be in action 30

to 40 days, depending on weather.

The sand is being deposited on an

old air strip, then moved and spread on “feeder” beaches at the Coast Guard

base. The idea is to let nature take its course, and allow the tides to move the

sand down the public beaches from Poverty Beach west to the Cove and on down to

the bird sanctuary in Lower Township.

Originally the Army Corps of

Engineers plan called for 360,000 cubic yards of sand for this phase of Cape May

beach replenishment. It was to have been accomplished, as it has in the past,

but piping sand from the ocean onto the beaches. However, the cost became cost

prohibitive, much more so than the government had estimated. That’s why it was

decided to truck in the sand at a cost of $2.3 million.

The Army Corps has been

replenishing Cape May beaches since 1989, when the original reconstruction

began, plus eight refilling projects about every two years.

The fact that there is less sand

available this year is viewed by some as positive since less sand produces a

more gradual slope, creating safer beaches for swimmers and surfers. In the

past, large sand deposits have resulted in tides digging out sudden steep

step-offs which have been blamed for recreational accidents.

There has been some concern voiced

about the quality of sand trucked in from sandpits. According to Project Manager

Dwight Pakan, the contractor Albrecht and Heun will supply clean sand from its

pits at Cape May Court House that meet specifications and will mix with existing

sand on the beaches. “The sand should be no different than what is now on the

beach,” says Pakan. “In 2000, we placed trucked-in quarry sand on Cape May Point

beaches with no problems.”

Some of Cape May Point’s beaches

that are protected by offshore breakwaters have become so stabilized, they are

now uneven with the beaches washed by ocean tides. These stabilized beaches

stretch 20-30 feet further into the water, and cause uneven footing for

swimmers.

Cape May Point officials have

asked the Army Corps to remove some of that sand and place it on the Meadows

(bird sanctuary) beaches. That contract was awarded December 10th.

Bulldozers and haulers are expected to complete the project by March 2009.

|